Building your world: dunes

- Book status: 165k

- Nov 22, 2016

- 10 min read

It has been ages since my last worldbuilding post. Sorry about that, these things take more time than I expected. Let's get ready for this lecture, shall we?

Dunes probably make you think about deserts, but they occur everywhere as long as the wind can move sand particles. They come in different sizes, from knee-high bumps to monsters rising hundreds of metres up in the sky. The biggest one is Duna Federico Kirbus in Argentina, being 1230m high!

To explain the life of a dune, we must start much smaller: a flat sandy surface. Landscapes are dynamic, but sand is particularly movable. As soon as the wind is above a certain threshold, sand will be picked up by it and move around. Sand can roll over the ground, or fly high up in the sky, where it can travel great distances - even get to other continents (maybe you've heard of 'Saharan dust')! Okay, technically, those particles are so small that you can't call it sand any more, but you get the idea. Most particles don't do either of these transport mode, but something in between: they hop over the surface, a process called saltation. You can feel that process very well when you walk over the beach with strong winds and with short trousers: sand bombards your skin, as if the air is made of sandpaper!

Sand has a habit of organising themselves into regular features as soon as it moves. They form patches, which, if they are lucky, grow further into protodunes - baby versions of dunes. The very first steps of sand getting transported by the wind and forming something bigger is a topic that still gets researched (by yours truly, amongst others).

Dune growth gets also initiated by debris or plants: something that allows the sand grains to 'take cover' from the wind. Obstacles slow down the wind, which lowers its transport capacity. The dunes that form behind those obstacles are called 'incipient dunes' or 'shadow dunes'.

How long does it take before a dune reaches adulthood? Well, I don't have a solid answer to that. It depends on the size of the dune, the weather and topography. I guess many, many years.

Even adult dunes are busy things: they like to roam. Sand gets eroded at one side by wind, gets transported over the rim, only to be dropped at the other side, where it avalanches down the slope (with 'avalanche' I don't mean one of those big, epic events you can find on snowy mountains. These are rather cute). This causes the dune to move, slowly but steadily. How fast a dune is depends on many things, but bigger usually means slower.

Dunes 'die' when the sand does not move anymore. Usually, either there isn't enough wind to cause them to move or their sand supply gets disrupted. They can flatten out, or be taken over by vegetation. Or they'll just stand there, doing absolutely nothing.

Dune terminology

Dune foot - pretty straight-forward: its where the dune slope begins. In the Netherlands, we use a rather strict definition: it's 3 m above sea level. Yeah, I don't think I agree with that... But you need to have something. The exact position of the dune foot is not that easy to spot.

Dune crest - Yeah, that's the top. I wonder why I even put it here

Angle of repose - the angle of the slope of a pile of sediment that's just on the edge between stable and unstable. A gentler slope will be stable and perfectly fine, but a steeper slope will cause the sediment to avalanche down.

Slip face - the 'avalanche' slope of a dune.

Cross-bedding - if you cut open a dune, you can see layers of sand at an angle. This is because sand get transported over the dune crest and avalanches down the slip face, creating layers. You can see this so well when you look at sand stone that used to be a dune field.

Blowout - happens with vegetated dunes: a blowout is a gap in a dune row that lacks vegetation and the sand just 'blows out' to the area behind the dune row.

Dune types

Before I throw a list with dune types at you: dunes appear in more forms than I show here. They are often compound features, showing more than one dune-type trait. Really, you can write whole papers about that, but I'll keep it simple.

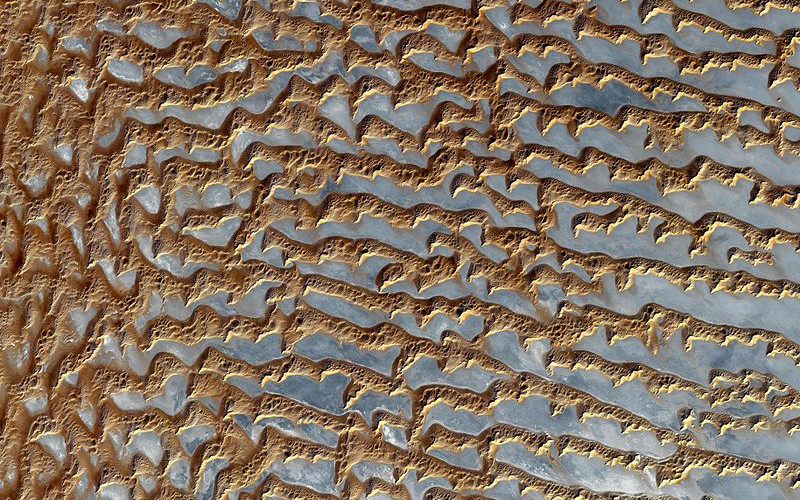

Cresentic/transverse/barchan dunes - these kind of dunes develop when the bed has little sand available. they are usually wider than they are long, with their arms pointing away from the dominant wind direction. They are very quick as well, moving with a velocity up to 100 m per year!

Lunnetes - dunes that form downwind of playas (dry lakes) and river valleys. They are made of the sediments found in the playa and riverbed, meaning they can be made of clay, silt or gypsum as well as sand.

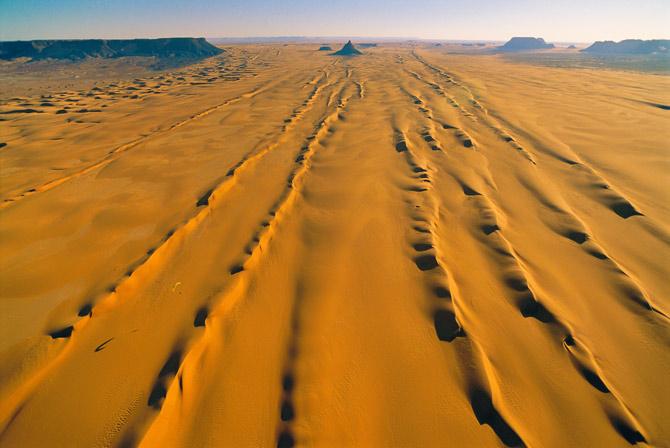

Linear/longitudinal/seif dunes - These dunes are much longer than they are wide. You need a wind climate with two dominant directions to get them. They can be perfectly straight, or show a sinusoid pattern. They can be pretty big, being hundreds of meters high and hundreds of kilometers long. Barchans can turn into seif dunes, after the wind direction has changed. This caused one of the arms of the barchan to grow much longer than the other, even overtaking the next barchan dune. If this wind becomes the new dominant one, the dunes will turn into barchans again, so it is important that the wind direction changes again to keep seif dunes longitudinal. 'Seif' means sword, by the way.

Star dunes - Biggest dunes out there, and their name describes pretty well what they look like. You need wind coming from many directions to get star dunes, which makes them grow upward. These dunes therefore do not walk around as much as the others.

Domes - These dunes lack a slipface, and therefore appear round or elliptic. They are rare, and form at the most upwind edges of sandy deserts.

Parabolic dunes - U-shaped dunes, with their arms point in the direction of the wind (so the opposite of a cresentic dune). Vegetation often anchors their arms. These guys appear in semi-arid to wet regions, since water is needed to stabilise these dunes. The wind almost always comes from the same direction here.

Transverse dune - Dunes whose crests lay perpendicular to the wind. They can form when barchan dunes merge together.

Nabkha or coppice dunes - Really small bump of sand, anchored by some vegetation. They are often a sign of desertification and soil erosion.

Coastal dunes - coastal dunes are the best, because I study them. I am totally not biased. Technically, they aren't any different than the dunes mentioned above in terms of shape (they usually come as parabolic dunes), but they have the sea to deal with. Storms erode them, creating steep sand cliffs, gaps in dune rows or keeping the dunes lower than they normally would be.

Dune vegetation

Okay, I am not an ecologist, so please don't ask me what plants grow in dunes. I only know the name of two: marram grass and sea hollies (and I only know this one because it is my favourite flower). However, plants do have a big impact on dunes. They catch sand, allowing the dune to grow but also stabilising it and keeping it from wandering around. Where there is no/less vegetation, the sand gets blown away, resulting in features like blowouts and coppice dunes.

Human impact

I can go on forever about this. Where nature is dynamic, humans try to keep things exactly as they are. Can't blame them: dunes have a habit of walking over towns and farmland, after all. Even a thin layer of sand can be enough to destroy harvests. Or, in case of coastal areas, we don't want to lose sand because we use it as a defence against the sea. Humans have tried various things to keep the sand where it is by building sand-catching fences and planting grasses. We now have a big 'sand dike' instead of a natural dune system in the Netherlands, thanks to centuries of taming our coast. Luckily, we see more and more often that there are other ways to keep the land safe and morphologically and ecologically interesting at the same time (in other words: we poke holes in our dunes, allowing sand to blow further landward and get the system more dynamic again).

What can you tell in your story:

A lot. I'll just name a few things that popped up in my head and write a terribly incoherent piece of text about it:

Dunes do not have terribly difficult terminology, so feel free to use it without explanation - a word like 'dune toe' has a pretty obvious meaning. Beware that that word is always used singular though: 'dune toes/feet' is not used!

Things get a bit more complicated with the type of dunes: to a character that doesn't know much about them, they all look like big piles of sand.

Dunes are usually not very useful to your characters. Their soils aren't fertile, except for small, low patches when the climate moist enough. Here in the Netherlands, you can't do much more with them than herding some sheep and growing a few potatoes. There has to be a good reason for your characters to live here. Maybe there is a sea close by, an oasis, or some kind of mine.

However, when the dunes aren't active anymore, you can flatten them and use them as farmland - then they will become very fertile. Guess where you can find the famous flower fields in the Netherlands!

Since dunes aren't that useful most of the time, your character is most likely to travel through them. Navigating through huge dune fields is tricky. Dunes look the same, and they are probably not well mapped either. You might have the sun to know your direction, but you still have to know where that one single oasis is. They disappear easily out of sight with dunes close by. Your character probably needs a guide, unless he knows the area.

Dunes come in various colours: reddish orange, yellow, pink, white, grey, black... It all depends on the source material they are made of. Young dunes appear less grey than older ones when they are vegetated though, because they contain less humus. Your character might find the white ones particularly annoying: if the sun is shining on it, they become really bright and hard to look at.

Most important thing of all: dunes are highly dynamic. THEY EAT PEOPLE. Okay, not really, but they do swallow villages. They move only slowly, but that's still faster than speed of the average house. Hmm, actually, I do know a story of a dune that ate a kid.

Rubjerg Knude Lighthouse, Denmark. Sucks to be it, I guess. The coastline retreats, so the building gets eaten by sand, and will be eaten by the sea pretty soon. This photo is an old one: the buildings you see have disappeared.

The wanderlust of dunes can be used in your advantage: you can use them to hide your gear. People know very well how fast dunes move, and used to hide their stuff at the lee side of them. The dune walks over them and voila! Your treasure is hidden. Come back a few weeks/months later and the dune has walked on, exposing the things you wanted to hide.

Sand can be very annoying. It gets everywhere, and it sticks to your skin - even when you are not sweating. Also, when the wind blows, the sand gets airborne, hitting your skin at high speeds. that hurts. If you are lucky, the saltating sand does not reach higher than your knees, but I've encountered situations where it hit my face more often than I would like (the stuff almost broke my camera during one of those occasions! it truly gets everywhere).

Besides getting everywhere, sand can get terribly warm as well when the sun beams down on it. At night though, the opposite happens: sand loses its heat quickly.

You can probably imagine that walking over a pile of sand is much more strenuous than asphalt, but it also allows you to do something really fun: sedi-surfing! You don't simply walk down a pile of sand, you slide down. Yay!

Maybe your world does not have dunes now, but maybe it used to have them. Sandstone shows beautiful cross-bedding when that's the case.

Dunes sing. Really. You can also call it whistling, booming or barking, depending on the dune. It doesn't happen often. You need sand of a certain grain size with a high silica content and a certain humidity. Beach sand can do this too, by the way. One theory that explains this is that sound waves bounce back and forth in the upper, dry layer of the dune. That strengthens the sound. You can't pinpoint where the sound comes from: the entire dune sings, even long after you set foot on it.

Will your POV character notice all of this? Probably not. Things he will notice quickly are:

sand being annoying and ending up all the way down into your underpants.

tiredness. Walking through sand isn't easy.

the colour, especially if it's something else than the typical pale-yellow sand usually comes in.

little ripples on top of dunes (the wind creates those).

the temperature; sand can be very hot, so hot you can't stand on it. You don't have to be in the desert for this, but it has to be a warm, sunny day.

sense of direction - or the lack of it. You get lost easily in sand seas. Deserts have a habit to be sunny though, that's quite helpful.

the sound, if the dunes sing.

If your character knows more about it, he will notice the other things as well, like the habit of dunes to move around, towns that get buried, how not to get lost, etc.

Do I have to use all of this?

Of course not. Like I said in my previous post, you should pick out a few things that make your landscape stand out. And the truly weird stuff, like singing dunes, might be a bit too tricky to mention in a simple area description. I mean: who is going to believe that dunes can sing, except for the random dune morphologist that actually knows about this stuff? You really must have seen it (or a youtube video) to believe it, Still, if you use it wisely... I can imagine the sound gets mistaken for snoring dragons! Your imagination is the limit.

Hmm, I guess that's it for today. Now, get yourself a sandbox and start shaping your world!

Also, if you want to know more about a landscape feature for the next blog, let me know! Except mountains or volcanoes. I'm not a geologist, I don't know much about those...

Comments